Exercise-Induced Pulmonary Hemorrhage (EIPH) isn’t new. This condition was first noted in the 1600-1700s within the world of Thoroughbred racing, where speed and power were revered. Those ancient bloodlines, including the hardiness of Arabian horses, now course through many of today’s top equine athletes. EIPH primarily occurs in racehorses—Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds, and Quarter Horses—due to the demands of quick acceleration and intense effort. However, EIPH is also common among other high-performance equine athletes, including those in cutting, reining, barrel racing, roping, polo, cross-country, three-day eventing, show jumping, hunter-jumper, steeplechase, dressage, endurance, and draft pulling. While severity often increases with the intensity and duration of effort, EIPH can even occur at moderate speeds. Ironically, some of the most talented athletes seem to be the ones most affected. This is due to the delicate balance between a horse’s powerful heart and relatively modest lungs, making them all susceptible to EIPH.

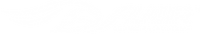

To understand why EIPH occurs, let’s look more closely at the horse’s athletic design and what happens when exercise intensity increases. Through selective breeding, horses have developed massive, powerful hearts capable of fueling intense athletic demands. As exercise intensity increases there is a need for increased oxygen intake and distribution to the muscles powering locomotion. To deliver the oxygen heart muscle contractions get stronger and heart rates increase to as high as 220 beats per minute pumping 75 plus gallons of blood through the lungs every minute.

The increased blood volume pumped is intensified by the horse’s natural ability to “blood dope”—resulting from splenic contraction--that increases the red blood cell concentration to carry more oxygen. However, this oxygen-rich, thicker blood is harder to pump, leading to exceptionally high blood pressure within the lungs. Blood pressure in horses’ lungs can increase four-fold during intensive exercise. Yet while heart and muscle development have prioritized speed and strength, the lungs haven’t evolved quite as robustly.

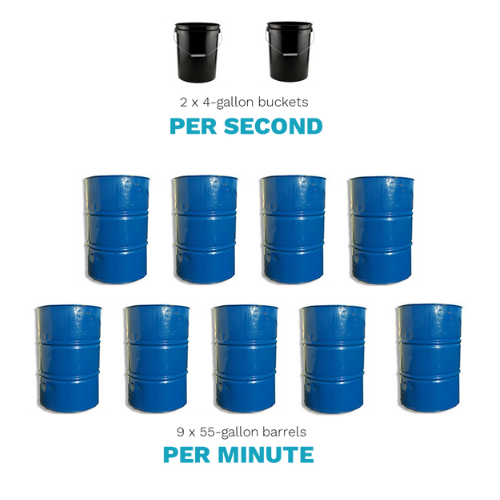

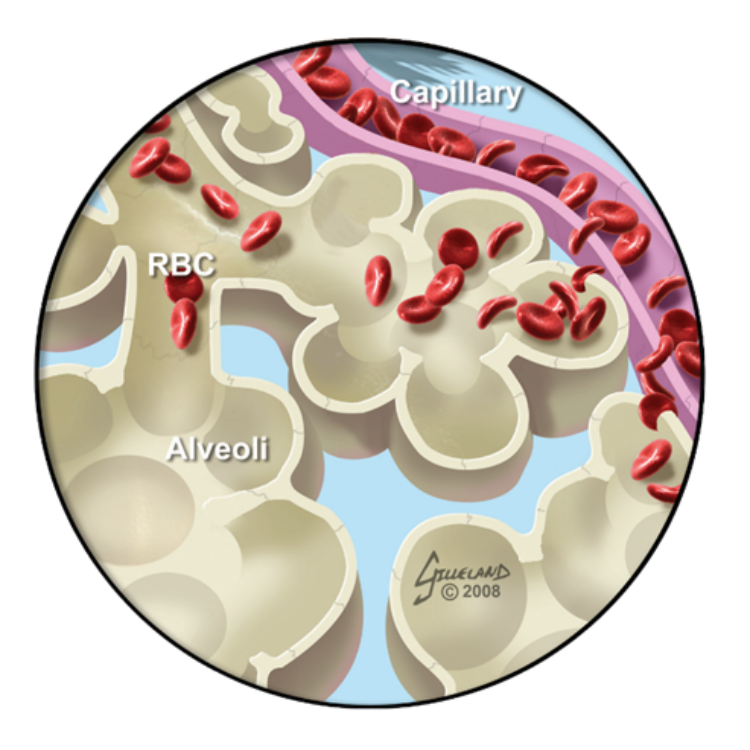

Deep within the lungs, the oxygen containing air that is inhaled through the nose travels to the alveoli where it diffuses across the fragile blood gas barrier (the pulmonary capillary membrane or “PCM”) where it binds to the hemoglobin in the red blood cells passing through the small capillaries in the lungs. From these capillaries the blood is carried back to the heart to be pumped throughout the body to the muscles and other tissues that power locomotion.

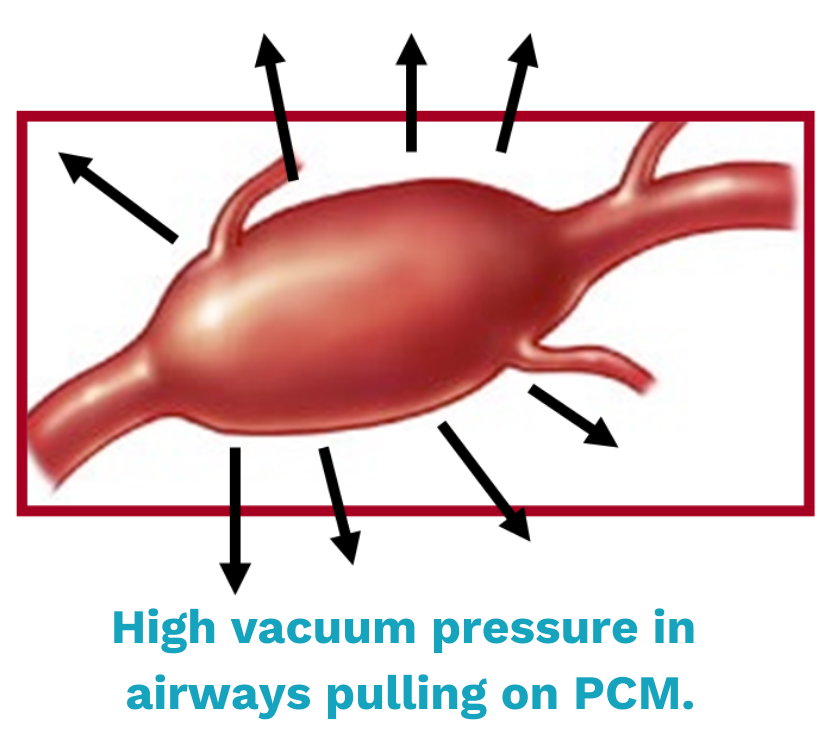

When galloping, a horse’s breathing and stride are linked. With each powerful stride, the horse inhales forcefully creating a vacuum effect to draw in 120-140 breaths per minute. And, because horses are obligate nasal breathers, air can only come in through their nose. The strong vacuum pressure causes the unsupported soft tissue in the nasal passages to partially collapse, increasing airflow resistance. The combination of forceful inhalation with collapsing airways add incrementally to the stress put on the respiratory system, especially as speeds increase.

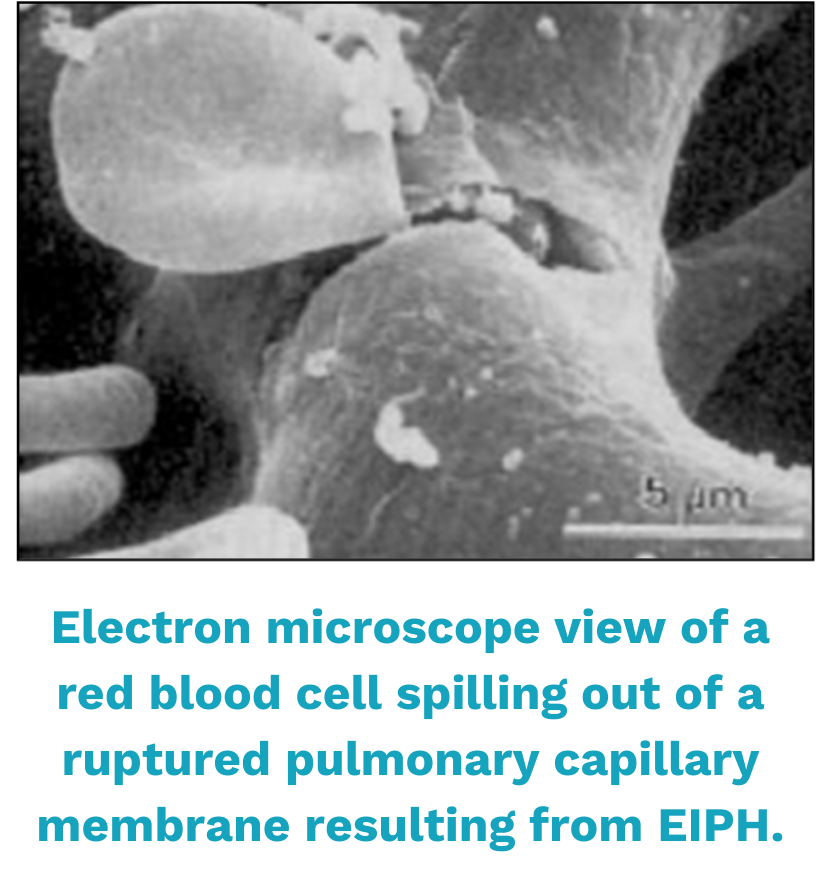

The pulmonary capillary membrane (PCM) separates the pulmonary capillaries from the alveoli deep within the lungs. The PCM is 1/100th the thickness of a human hair, meaning it’s very efficient at transferring oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs, but is very fragile.

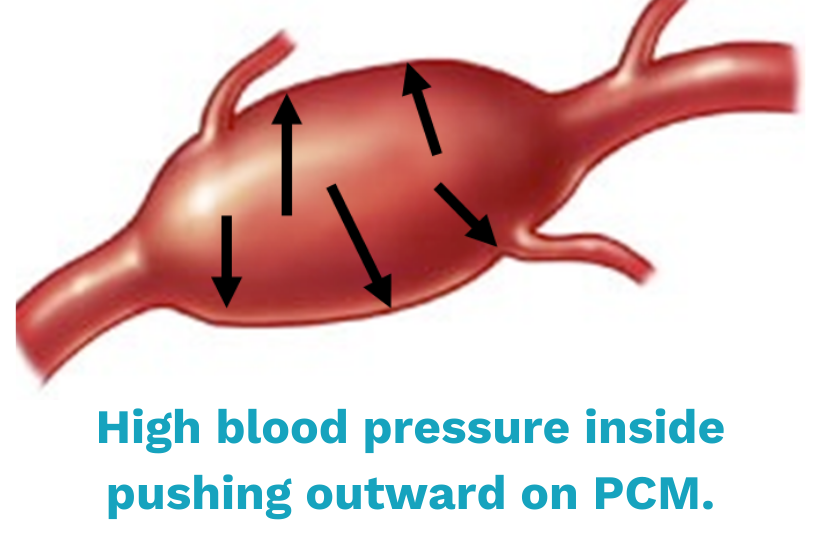

During intensive exercise the high blood pressure in the lungs pushes outwardly on the PCM from inside the pulmonary capillaries while the high vacuum pressure pulls on the outside of the PCM. The combined stress of the pulling and pushing on the PCM causes it to rupture releasing blood cells into the alveoli resulting in EIPH.

|

|

|

Simultaneously, each hoof strike sends vibrations up the limbs and across the shoulder blade, penetrating the chest and placing additional stress on the delicate blood vessels in the lungs. Further adding insult to injury, exercising blood flow is preferentially directed toward the upper and back portions of the lungs, which are particularly susceptible to damage. Over time with repeated episodes, the tiny veins in these regions undergo remodeling, leading to scarring, iron deposits, and thickening of the vessel walls. This narrowing further raises blood pressure in the lungs, compounding the risk of vessel rupture. Together, the combined action of these forces converges on the fragile pulmonary capillary membrane, causing tiny blood vessels to rupture and leak blood into the airways—a condition known as EIPH.

When cardiovascular issues are present, they can exacerbate EIPH. Irregular heart rhythms, such as atrial fibrillation, valve leakage, and insufficient heart muscle relaxation at high exercising heart rates disrupt the filling of heart chambers and can further elevate blood pressure in the lungs. These conditions amplify the stress on lung blood vessels, increasing the likelihood of EIPH and its detrimental impact on a horse’s performance and health.

Upper airway conditions that cause upper airway obstruction can also exacerbate EIPH. These include, for example, dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP), laryngeal hemiplegia (LH or "roaring"), soft tissue instability, masses in the upper airways, and rider-induced hyperflexion of the head and neck. These obstructions partially block the airway, reduce its diameter, and create turbulent airflow, forcing horses to work harder to breathe. As obligate nasal breathers with long windpipes, horses already face airflow limitations, and these obstructions further intensify the vacuum effect on the delicate blood vessels, increasing the risk and severity of EIPH. Overground exercise endoscopes may help to identify clinically relevant upper airway obstructions including dorsal displacement of the soft palate and laryngeal hemiplegia.

One of the more challenging aspects of EIPH is that, often, the problem begins insidiously as horses begin their competitive careers. It might be so minor at first that it’s hardly noticeable, a minor leak in the delicate lung tissues that doesn’t impact performance. But over time, with each strenuous workout or competition, the bleeding can become more frequent and more severe. Effects become cumulative and progressive as the effected portion of the lung continues to move from the back forward, encompassing more and more of the lung. Scar tissue from repeated episodes begins to alter the architecture of the lungs, reducing their elasticity and, ultimately, their efficiency. Large volumes of blood from acute episodes along with scarring and thickening of blood-gas exchange regions can lead to reduced performance and stamina or “exercise intolerance” as impaired gas-exchange from the lungs makes it a struggle for the circulation to deliver enough oxygen to the muscles. For high-level athletes, this early fatigue can mean the difference between winning and falling short.

Inflammation plays both a causative and consequential role in the severity and progression of EIPH. When blood enters the lungs, it doesn’t simply disappear; immune cells work to break it down for clearance, but they can become overwhelmed, leaving behind incomplete cleanup and lingering inflammation that worsens bleeding through a vicious cycle of damage. Furthermore, different types and levels of exercise cause differing effects on inflammation and declining immunity of lungs. Exposure to respiratory irritants—such as poor-quality air, airborne pollutants, respiratory viruses, and the dust, molds, and endotoxins found in hay—further inflames the airways. Inflammation, regardless of cause, can lead to mucus buildup that impedes airflow and permanently damages airways, decreases lung compliance, and blunts gas-exchange efficiency, as a result of scarring that heightens the risk of EIPH during future exercise bouts, as well as impairing performance and increasing susceptibility to infections. Treatments targeting inflammation show promise in boosting immunity and delivering anti-inflammatory effects that help break this harmful cycle.

At its core, EIPH is a natural byproduct of the horse’s athletic design—a complex physiological adaptive response that can become a disease. Lower levels of EIPH may not have much impact on performance, but for horses that bleed more severely, EIPH can interfere with their endurance, cause early fatigue, and, over time, may shorten their competitive careers. And while it’s a sobering diagnosis, there are effective management strategies to support a horse with EIPH, helping to ensure their health, performance, and well-being as they continue to do what they love.

In a way, EIPH reflects the strength and power that fuel our equine athletes. Through knowledge and by protecting lung health—the key limiter of equine performance—owners can make informed decisions to support these extraordinary partners, ensuring they can safely pursue the intense athleticism for which they were born.