Equine Insights: What Causes the Development of Kissing Spines | Part 2 of the Kissing Spines Series

Posted by Dr. Hilary Clayton on Oct 4th 2024

Part two of the deep dive into the reality of kissing spines.

We learned last time that kissing spines is a potentially painful disease in which the spines of the vertebrae rub against each other. Let’s take a look at what causes the development of kissing spines.

What causes the development of kissing spines?

It occurs most often in Thoroughbreds, Warmbloods, and stock horses, which include Quarter Horses and Paints. Recently, it has been found that genetics play a role, and at least two genes affect a horse’s susceptibility to kissing spines and the severity of the disease if it occurs.

In the withers regions, the spines are narrow with relatively wide spaces between them, but behind the withers, the spines broaden, and the spaces get more narrow. The narrower spaces are a risk factor for the development of kissing spines. Horses with poor posture, specifically those that stand and move with a hollow back, called lordosis or a lordotic posture, are more likely to develop kissing spines than those with good posture with a more rounded topline.

Figure 1: Compare the shape of the toplines of these two horses. The horse on the left has good posture and a normal back shape. The horse on the right has poor posture with a hollow back which is a risk factor for developing kissing spines.

Movement in the spine.

Doing back lifts with a horse by applying pressure or scratching the horse under his ribcage in the area of the girth line stimulates the horse to tighten his core muscles and raise his back. As the back rises, the spines are separated in the region from T5 to T18.

The joints between the vertebrae undergo small amounts of motion that vary along the length of the spine and are different in each gait. At the walk, most of the motion is lateral bending; as a hind limb moves forward, it pushes the barrel to the opposite side, so the horse’s back becomes concave on the side of the advancing hind limb. In trot and canter, the main movements are flexion and extension due to the bouncing motion associated with the presence of suspension phases. The back rounds when the horse is airborne during suspension and hollows during the weight–bearing phase. When the horse’s back hollows, the adjacent spines rotate toward each other, increasing the likelihood of impingement.

The effects of a rider.

The weight of a rider sitting on a horse’s back causes the back to hollow. This is most easily seen as a downward slope from the top of the croup to the back of the saddle (Figure 2). A heavier rider causes greater extension of the back. The effect of the rider’s weight is much greater in trot and canter than in walk due to the bouncing motion in the suspension phases. At the trot, the maximum compressive effect of a rider on the horse’s back is double the rider’s weight. The effects of the rider’s weight in hollowing the back can be somewhat ameliorated by strengthening the horse’s core muscles and teaching the horse to maintain good posture with a rounded topline.

Figure 2: This photo was taken at the moment when the rider’s weight has the greatest effect in hollowing the horse’s back in the canter. The yellow arrow indicates the downward slope of the back from the high point at the croup as it descends toward the back of the saddle.

Common locations of kissing spine lesions.

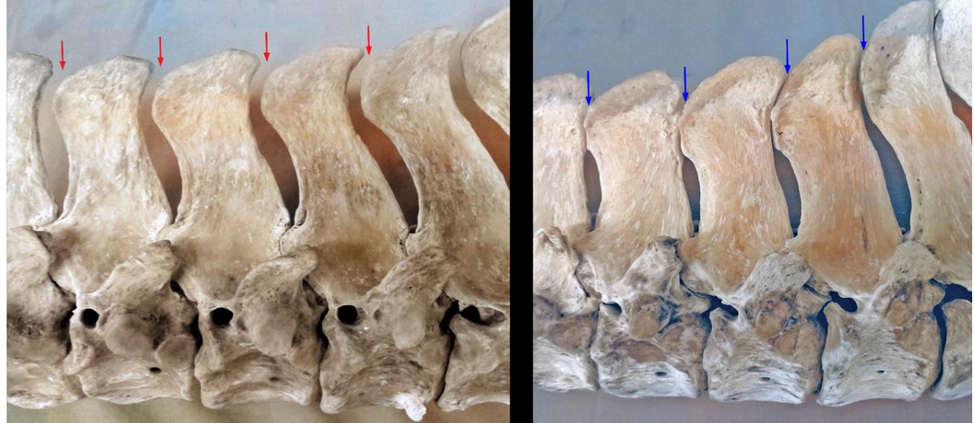

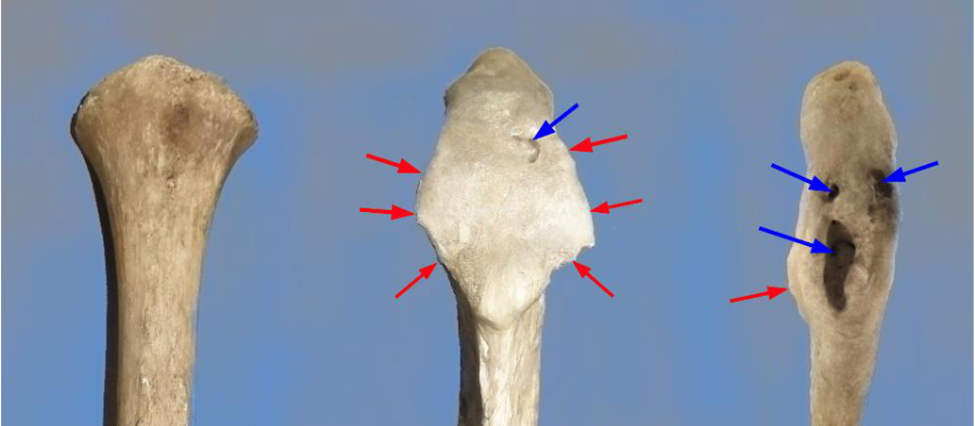

The predisposing factors listed above, poor posture, the shape of the spines, and the effect of the rider’s weight, all suggest that kissing spines are likely to affect the part of the back where the rider’s weight is concentrated. This was borne out by a study of 33 horse cadavers in my lab at Michigan State University. Although we found some degree of kissing spines at every vertebral level in the thoracic and lumbar regions, most severe lesions were present between T11 and L1, representing the region beneath the saddle. The lesions were more severe in taller horses. Examples of kissing spine lesions are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Side view of vertebrae T12-T15 from two horses. On the left, the spines of the vertebrae are well separated along their entire length (red arrows). On the right, the upper parts of the successive spines are impinging (blue arrows). The horse’s head is to the right.

Figure 4: The tip of the dorsal spinous process viewed from behind shows a normal spine on the left and lesions associated with kissing spines in the center and on the right. Red arrows point to osteophytes indicating new bone formation, and blue arrows point to areas of bone loss that appear as lucent areas on an x-ray.

Now that we have covered both the anatomy and what causes the development of kissing spines, stay tuned for part three. In the next blog, Dr. Hilary Clayton will cover the veterinarian’s role.

Do you still need to read part one of this three-part series? No problem! Check out our first part of the series HERE to learn more about the anatomy of the equine spine and kissing spines.

Who is Dr. Hilary Clayton? Learn More!