Equine Insights: The Veterinarian’s Role with Kissing Spines | Part 3 of the Kissing Spines Series

Posted by Dr. Hilary Clayton on Oct 24th 2024

Welcome to part three of the deep dive into the reality of kissing spines.

Horses afflicted by kissing spines become more painful when ridden because the rider’s weight causes their back to hollow and presses the spines closer together. The horse tries to reduce back movements by tensing the muscles; as a result, the back stiffens and ceases to swing.

It doesn’t take long for a horse to realize that pain is associated with having the tack on, and this may lead to an aversion to being saddled with the horse moving away, pulling ugly faces, and even trying to bite. The horse may show resistance or bad behavior during and after mounting, including reluctance to move forward, bucking, and rearing. These signs are not specific to kissing spines. They can also be due to other causes of back pain, such as an ill–fitting saddle, so it’s a good idea to check your saddle as soon as signs of back pain occur.

Consult with your Veterinarian about Kissing Spines

Make sure to tell your veterinarian about changes in your horse’s behavior during tacking, mounting, and riding because these will factor into the diagnostic process. The clinical examination at rest may reveal tenderness on palpation of the spines, reduced back movements in flexion, extension, bending, spasm of the back muscles, or back muscle atrophy. It’s best not to medicate your horse for a few days before the veterinary visit to avoid hiding these signs.

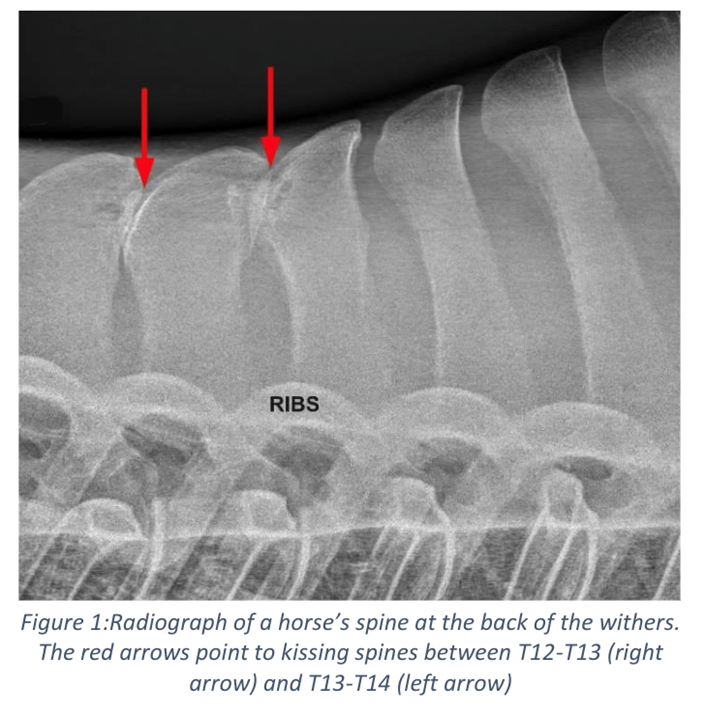

A diagnosis of kissing spines is usually confirmed radiographically (Figure 1) by the presence of narrow or non–existent spaces between adjacent spines, sometimes with the presence of bone spurs (osteophytes) or lucent areas representing cavities within the bone. Ultrasonography and scintigraphy are also sometimes used diagnostically.

The Diagnosis and Treatment: The Veterinarian’s Role with Kissing Spines

One of the interesting features of kissing spines is that the degree of pathological change is not indicative of how much pain the horse feels. Some horses showing only mild pain have severe radiographic changes, whereas other horses with relatively slight radiographic changes are markedly painful.

After confirming the diagnosis of kissing spines, your veterinarian will recommend treatment based on several factors, including the location and severity of the impingements, the rider’s goals, and financial considerations. Since the recommendations vary from case to case, I’ll give only a general outline of treatment methods.

The First Line of Treatment with Kissing Spines

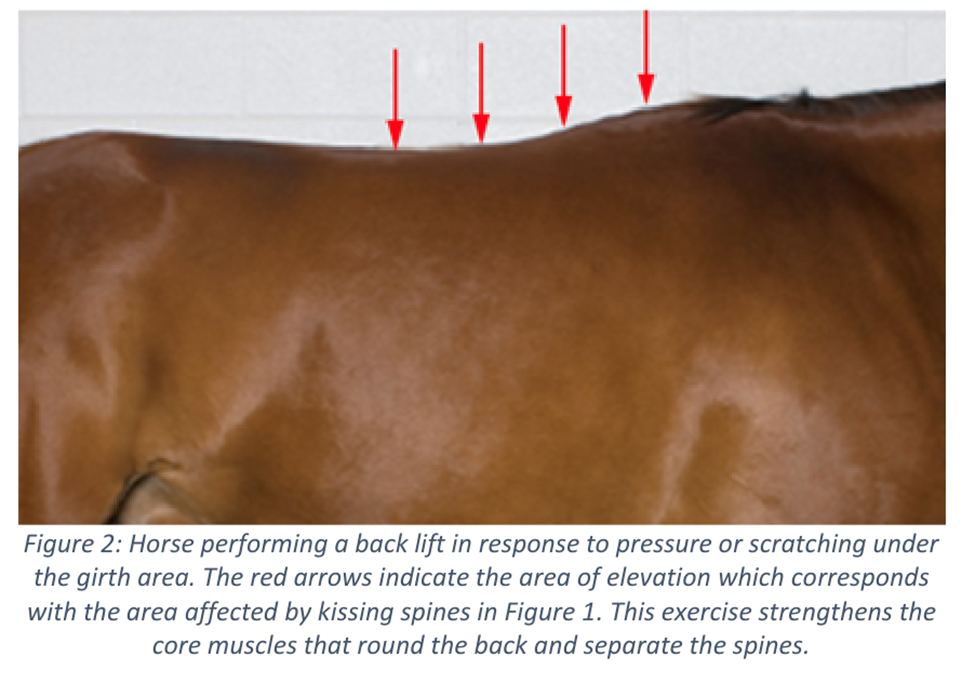

The first line of treatment is often a course of oral anti–inflammatory medication combined with core training exercises (Figure 2) to strengthen the muscles that round the back and improve the horse’s posture. Working the horse in a low and rounded outline helps to round the back. Therapeutic exercise equipment teaches the horse to carry himself in a more rounded outline. During the early stages of therapy, exercising the horse on the lunge without a rider for a few weeks may be helpful. In some cases, these interventions may be sufficient to resolve the signs.

Several treatments may be used to reduce pain. These include corticosteroid injections between the impinging spinous processes to calm the inflammation. This treatment usually has a good response rate, with up to 90% of horses responding positively. Unfortunately, clinical signs are likely to recur in about half of these cases, so repeated treatments may be needed.

Remember to check with your veterinarian whether prescribed medications are allowed in competitions and, if not, what are the withdrawal times or are there alternative medications that can be used during competitions.

Other pain-reducing treatments include shock wave therapy and mesotherapy. Muscle relaxants may reduce painful muscle spasms. Physical therapy, acupuncture, and chiropractic treatments may also be beneficial.

Kissing Spines Surgeries

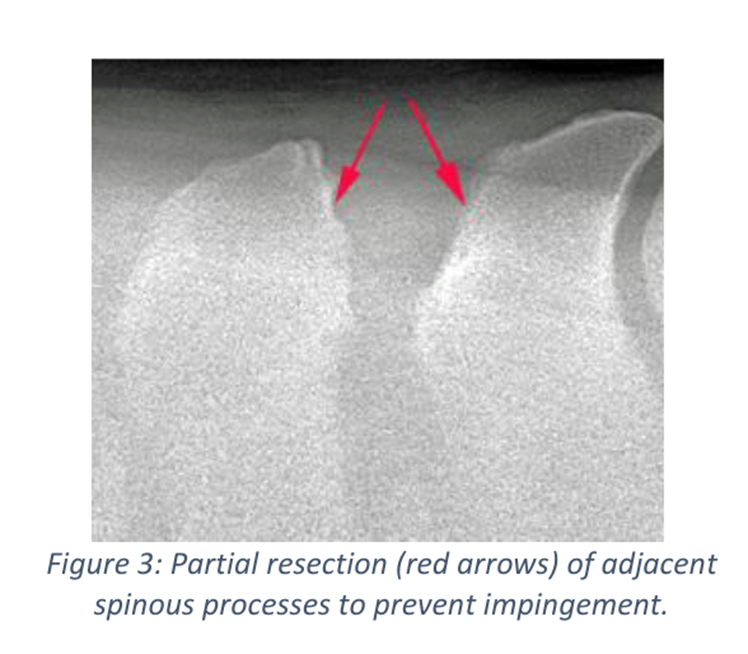

Surgery tends to be used as a last resort to treat kissing spines. The original surgical treatment removes the summits of alternate spines in the affected area. It has been reported to allow 72% of treated horses to return to their previous level of ridden work. A variation on this technique removes a triangular wedge of bone from the top of the affected spines (Figure 3) and has the advantage of causing less tissue disruption.

In a newer, less radical surgery, called inter–spinous ligament desmopathy, special scissors are used to cut the inter–spinous ligaments that run between the affected spines while leaving in tact the supraspinous ligament that connects and stabilizes the tips of the spines. Horses with kissing spines have abnormal interspinous ligaments that show changes in the composition and orientation of their fibers, together with an increased nerve supply that maybe a source of pain in some horses. In one study, back pain resolved permanently in 95% of horses treated by inter–spinous ligament desmopathy. This surgery has a shorter recovery and faster return to work compared with spine resection.

Kissing spines is the most common disease of the vertebrae in horses, and it can be extremely painful. However, there is a range of medical and surgical treatments that can alleviate pain and often allow the horse to return to an athletic career.

This concludes the three-part kissing spines blog series by Dr. Hilary Clayton. Previously in parts one and two, Dr. Hilary Clayton covered the anatomy and what causes the development of kissing spines.

Who is Dr. Hilary Clayton? Learn More!