Equine Insights: The Trunk – How to Better Understand your Horses Back Biomechanics

Posted by Dr. Hilary Clayton on Aug 30th 2024

Each part of the locomotor apparatus plays a distinct and different role in locomotion. The horse’s trunk is the central part that unites and coordinates the haunches with the forehand. In addition to transmitting propulsion forward from the hind limbs, the trunk supports the body organs and carries the rider’s weight. In my previous post, we looked at how the different body parts work together to produce the horse’s extraordinary athletic prowess.

Diving into the biomechanics of a horse and the equine back defined. These functions require strength, stability, and mobility in just the right proportions. This article will focus on the spine and how it fulfills these functions.

What is the Trunk?

Twenty-four vertebrae support the trunk, 18 in the thoracic region (T1 to T18) and 6 in the lumbar region (L1 to L6). Between each pair of vertebrae are the inter-vertebral disks that act as a cushion when forces are transmitted along the length of the spine. The individual vertebrae are joined together by tough ligaments, muscles, and tendons to form the spinal column. The joints between each pair of vertebrae allow only a tiny amount of movement, but this is sufficient for the back to round and hollow, bend left and right, and twist along its length.

The Delicate balance between Strength, Stability, and Mobility of the Trunk & Vertebral Column.

There’s a delicate balance between strength, stability, and mobility. If the vertebral column were completely rigid, it would provide excellent strength and stability. Still, the horse would not be able to bascule or bend, and the lack of cushioning between the vertebrae would make riding darned uncomfortable! On the other hand, if you had a horse with intervertebral joints that were excessively mobile, the spine could not provide enough stability to transmit propulsion forward from the haunches.

Conformation of a Horse’s Back + The Benefits of Long & Short There’s Horses.

Conformationally, differences in the length of the horse’s back are not due to variation in the number of vertebrae but rather to differences in the size of the individual horses. Horses with longer vertebrae can show more lateral displacement than a horse with shorter vertebrae for the exact change in angle. Therefore long-backed horses are easier to bend. The trade-off is that a short back is more robust and easier to maintain in a rounded shape.

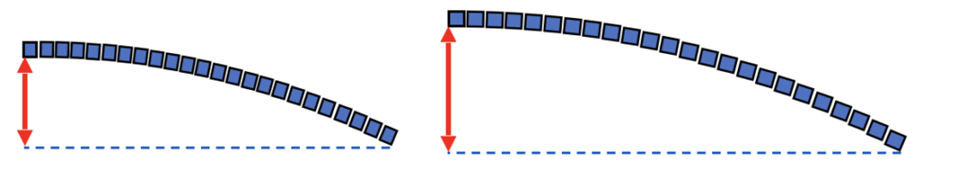

A Visual Bend of the Horse’s Back

These two diagrams show the horse’s back as if you were looking down from above. Each blue block represents one of the horse's vertebrae that span the distance from the horse’s limbs on the left to the hind limbs on the right of the diagram. The back is bending to the left by one degree at each intervertebral joint. The haunches’ displacement to the side, shown by the red arrows, is more significant for the long-backed horse on the right than the short-backed horse on the left.

Short vs. Long Equine Back

The horse on the left has a short, strong back. The horse on the right has a long, relatively weaker back. Note the difference in both the top line and the underline. The extra length is most evident in the loin region.

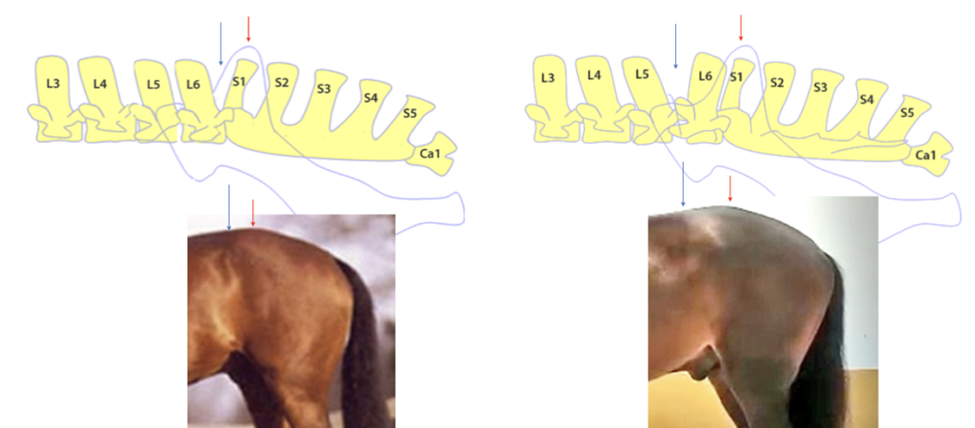

Sometimes the last lumbar vertebra is attached to the front of the sacrum, so there are effectively only five lumbar vertebrae. Folklore says Arabians are prone to having one less vertebra in the back, but this anomaly can occur in most breeds and may be advantageous in some sports.

A Normal Lumbar Vertebrae and Sacrum vs. a Fused L6

The lumbar vertebrae and sacrum of a horse with the average number of 6 lumbar vertebrae on the left and a horse in which the sixth lumbar vertebra is fused to the front of the sacrum (right). The blue arrows indicate the divergence of the spines of the vertebrae between L6 and S1 on the left and between L5 and L6 on the right. This is the site of the lumbosacral joint, which is highly mobile in flexion/extension and lateral bending. The gray outline on the diagrams shows the pelvis with the red arrow pointing to the sacral tuberosity, the highest point on the croup.

Note the distance between the blue and red arrows in the two diagrams and the corresponding photos; when the lumbosacral joint flexes, the fusion of L6 to the sacrum allows more significant pelvic tilting in the horse on the right. This lengthens the galloping stride by rotating the hind limb further under the body and facilitates the lowering of the haunches in highly collected movements, such as piaffe and pirouettes.

How this Affects the Equine Training Process + Injury Prevention

During training, we focus on developing flexibility and suppleness of the back so the horse can round and bend equally to the left and right sides. These are essential skills for sporting performance, but in terms of injury prevention, the ability to stabilize the spine during locomotion is a high priority for injury prevention.