Equine Insights: How the Equine Shoulders Affect Performance

Posted by Dr. Hilary Clayton on Nov 18th 2024

In this blog, I will describe the horse’s chest and shoulder region focusing on how they differ from our own and the implications this has for locomotion and performance.

Locomotion is defined for humans.

People are bipedal – we walk on two legs with our bodies in an upright posture. During the transition to bipedal locomotion, the forelimbs evolved into arms and hands with opposable thumbs enabling us to perform tasks that require dexterity and fine motor coordination. We don’t use our arms and hands for weight-bearing during locomotion though if our arms are not busy doing something else, we can swing them in a diagonal pattern with our leg movements as a way to control body rotation.

The Human Collar Bone.

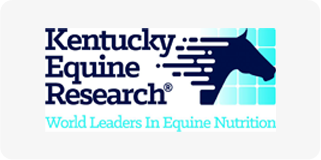

The shoulder region also underwent some significant changes to accommodate bipedalism. Our ribcage is narrow from front to back but wide from side to side. The triangular shoulder blades (scapulae) lie flat on the back of the chest with the shoulder joints forming the widest point at the top of the chest.

The collar bone (clavicle) crosses the front of the chest above the first rib. You can easily feel it as a bony ridge that connects the sternum to the scapula close to your shoulder joint.

Figure 1: Human chest viewed from in front with the collar bone shown in blue.

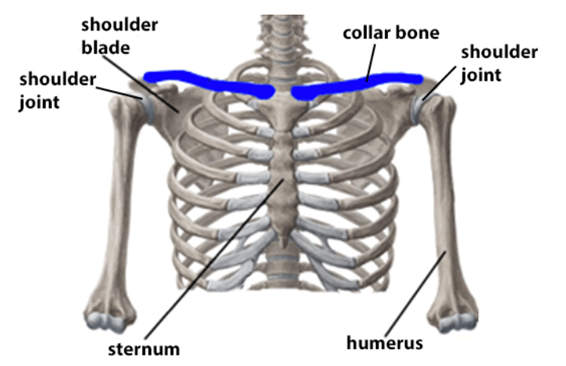

The impact your clavicle could endure when falling off a horse.

One of the functions of the clavicle is to transfer forces from the arm to the ribcage and the rest of the body. If you fall with your arm outstretched to break the fall, the impact of landing is transmitted through your arm to the clavicle which is a weak link. Most riders know someone who has broken their clavicle in a horse–related fall, often in the manner shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Falling onto an outstretched arm will likely fracture the collar bone.

Let’s define what locomotion looks like in horses!

Horses are quadrupeds, meaning they use all four limbs for locomotion. The hind limbs are the motor that provides most of the propulsion. The forelimbs are responsible for braking and turning, which will be discussed in a future blog.

The horse’s ribcage is flattened from side–to–side and the chest is deep but relatively narrow. The scapulae lie on each side of the chest and the shoulder joint is close to the point of the shoulder at the front of the chest. The humerus connects the shoulder and elbow joints (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The horse has a deep chest with the scapula and humerus

on the side of

the chest at the front of the

ribcage. The red line indicates the angle of the scapula.

The anatomical difference between horses and people is defined.

A major anatomical difference between horses and people is that horses do not have a clavicle. This means no bones connect the forelimb to the ribcage and the rest of the body. Instead, the horse’s forelimb is attached by strong muscles, tendons and ligaments. The lack of a clavicle allows the horse’s scapulae to slide and rotate on the side of the chest.

Let’s test out how the equine shoulders affect performance!

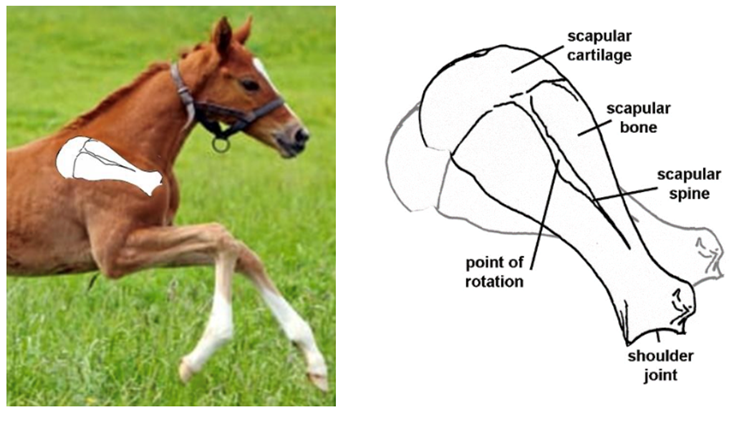

Try this: Pick up one of your horse’s forelimbs and lift it forward as high as possible then pull it back as far as possible underneath the horse’s body. Watch how the angle of the scapula changes. If two people are available, one person should move the limb while the other puts their hand on the skin over the scapula to feel how it moves beneath the skin. The entire scapula rotates around a point just above the middle of the bone. When the top part of the scapula rotates back and down, the lower part rotates forward and up (Figure 4).

The foal in Figure 4shows the scapula maximally rotated and illustrate show this elevates the shoulder joint and allows the elbow joint to be pulled forward so the lower limb can swing more freely.

Figure 5: This photo shows the moment when the forelimb is maximally forward and elevated in trot. The point of the shoulder is elevated (red arrow), and the elbow joint is forward well in front of the girth line (blue arrow).

In Figure 4 The dark image on the right shows the main features of a horse’s scapula. When it rotates into a more horizontal position, shown in the light gray image, the top of the scapula moves back and down while the lower end moves forward and up. This raises the shoulder joint so it is high on the front of the chest. In the image of the foal on the left, the scapula has rotated into an almost horizontal orientation with the shoulder joint high on the chest and the elbow pulled forward.

Why is the movement of the scapula important in our equine athletes?

Movements of the scapula are important both functionally and aesthetically. In dressage horses, the forward-upward motion of the elbow and lower limb gives the stride more expression (Figure 5). Rotation of the scapula into a more horizontal position allows the elbow to swing forward and raise the lower part of the limb.

Rotation of the scapula of horses when Jumping.

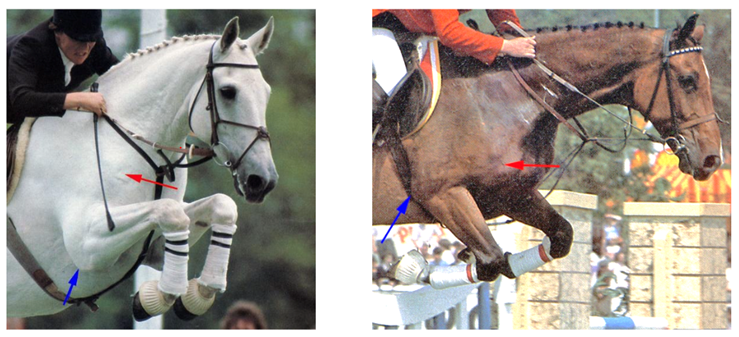

In jumpers, rotation of the scapula and forward movement of the elbow are prerequisites for the horse to raise the forearms and lift the knees and lower limbs over a fence as shown by the horse on the left in Figure 6. The horse in the photo on the right has not rotated the scapula or pulled the elbow forward and is unable to raise the knees.

Figure 6

In Figure 6 the photo on the left is a great example of a horse rotating the scapula and elevating the shoulder joint so it is close to the base of the neck. The humerus is almost vertical, pulling the elbows forward. Thus, placing them in front of the girth and allowing the forearms to be raised. In the photo on the right, the scapula has not been rotated horizontally and the shoulder joint is low – look how far it is below the base of the neck. The humerus is almost horizontal and the point of the elbow is over the girth. With the elbow in this position, the forearms cannot be raised and horses that jump in this posture are likely to pull a lot of rails.

Circling back to how the equine shoulders affect performance – We can see from these photos that, although our eye is often drawn to the lower limb movements, the freedom of movement in the shoulder and elbow region determines the range of motion in the lower limb.

In conclusion, the equine anatomy is a complex system. Each muscle has a special job to support the horse’s physical performance. To learn more about the equine anatomy check out our previous Equine Insights™ by Dr. Hilary Clayton blog posts!

Who is Dr. Hilary Clayton? Learn More!